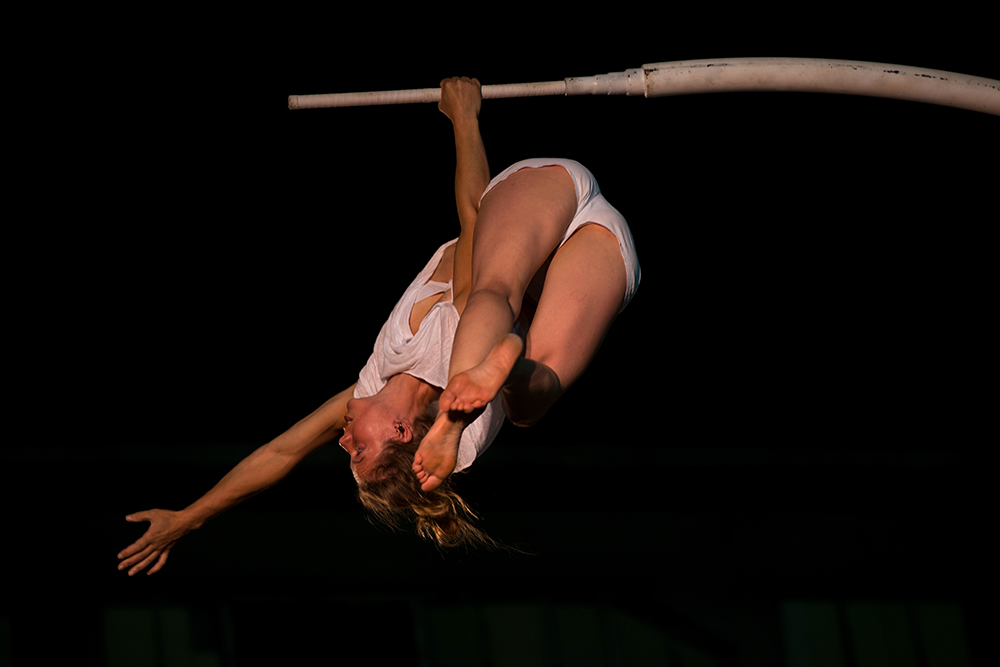

Chloé Moglia, the Suspensionist

Isabelle Merminod and Tim Baster capture the callisthenic poetry of French artist Chloé Moglia whose perches over her six-metre high metal frame can only be described as ‘suspension in disbelief’. Dangling, with no nets, from a bar that barely snakes its way around her body, Moglia relies only on her coarse, callused hands and strong arms as she defies gravity, and indeed, mortality. This is meditative circus at its finest, oscillating between the harrowingly nerve-wracking to the subliminally beautiful. A graduate of France’s acclaimed Centre National des Arts du Cirque, Moglia combines the ‘physical strength of an Olympic athlete and the grace of a ballet dancer’, seeking a form of higher consciousness for herself and for her audience.

Chloé Moglia mesmerised the public in four renditions of her display entitled ‘Horizons.’ on June 7 in Syntagma Square, and June 8 at Peiraios 260. Moglia was in Athens for the Athens and Epidaurus Festival, which celebrates theatre, dance and music. She explained that she is neither a trapeze artist nor a circus performer. She hasn’t really got a name for what she does. ‘Suspensionist?’

When she did her studies at the circus school in France (Centre National des Arts du Cirque), she cried for two days when she was told she was going to train on the trapeze; she was terrified of heights. And there is no security mat underneath her. Also, the act has no music and no commentary.

“People ask me: ‘Why is there no security underneath me?’ But of course there is security, but it is not shown by external things. Security is in my head, it is in my body and it is in my perception. It is in my professionalism, in the lightness of spirit with which I try to work and to develop. That is real security. If a security mat is in place, this tells me that I can fall. But when I am head down, even with a security mat six metres below me, I must not fall. So using a security mat is lying to myself. The mat is not about my safety, it is about managing the anxiety of the people who are watching.I am very clear when I work that I will not fall; it is very clear. So I don’t need a mat and I don’t have one.”

Six meters up on the crescent-shaped cradle, her body creates a series of shapes that sometimes appear to defy the very connection with the metal bar which supports her.

“The show is not really about what I do. I think that is what I really love: it is what happens between everyone present. So people can be overwhelmed by anxiety, the fear of the void or of me falling, and they project these fears on to me. Others are calmer about the act and project this feeling on me. So it is a form of dialogue – a conversation between the sensibilities of the spectators and mine. It will be different for everyone.”

“Suspension itself, is like an entrance door to the world. But it is also a way of really entering into the heart of questions. Letting go and holding on? What is the void? What is weight? What is gravity?”

“You can look at it through the lens of physics as I myself did for a while. I read lots of books to answer the question: ‘What is it?’ You can also look at it through meditation techniques. This opens up a huge number of doors, and it is fascinating, I had the feeling of being alive, of progressing, of questioning. It is like being a child again: What? How? Yes it is joyful and alive.”

“You can look at it through the lens of physics as I myself did for a while. I read lots of books to answer the question: ‘What is it?’ You can also look at it through meditation techniques. This opens up a huge number of doors, and it is fascinating, I had the feeling of being alive, of progressing, of questioning. It is like being a child again: What? How? Yes it is joyful and alive.”

Moglia explains that training is on three different levels: The mind and the spirit; the emotional and the sensitivity; and finally the body.

She stresses that the aim is ‘mastery’ not ‘control.’ And the constant danger to guard against remains ‘thoughts that intrude into your head; the head is like a small bicycle, always racing away, always’. Training the body to be supple without ‘slowing down the little bicycle in your head’ will achieve nothing.

“I have a vague outline; I know more or less that I will do this and the other. I don’t know exactly in what order. Then when I get going I drop even this vague outline which I use every time. I know that I am going to go up on the rope … Finally I have to relax my arms. My arms have to descend so the blood can revitalise things. I play with this a bit, but at the same time I know where this is going. But it depends on the audience’s attention, the luminosity, the sky, the time of day … of all my being.”

Isabelle Merminod is a freelance photojournalist and Tim Baster is a freelance reporter. They focus on social and human rights issues. they are fascinated by Greek culture, customs and lives.