Ruth Padel: Poet of the Labyrinth

A poet, writer, conservationist, musician, archaeologist and Hellenophile, Ruth Padel is someone with the willingness to engage with the big issues, both personal and political. The vast range of her imagination, intellect and emotional sympathies embrace the worlds within this world and the need for connectivity between them: the bonds between ancient and modern, art and science, and our need to ally more closely with nature and each other. Fascinated by words and music, she is chiefly a poet, with 12 award-winning volumes so far. Her many books also span non-fiction and poetical novels. She speaks to Ian Collins, Runciman-award winning biographer and curator at Athens Insider’s Literary Salon in May 2023, on her latest novel, Daughters of the Labyrinth, and the little-known Holocaust on Crete.

Ruth Padel in conversation with Ian Collins at the Athens Literary Salon organised by Athens Insider, as part of the Athens City Festival

So, Ruth, the book you would take with you to a desert island is Homer’s Iliad and you are also the great-great granddaughter of Charles Darwin whose theory of evolution evolved from a five-year voyage to South America. You yourself are a great traveller, but your overriding love of Greece began at home. How?

My father taught me ancient Greek when I was twelve. Then I did Classics at Oxford, as he and both my grandfathers did, and I went on to do a PhD in ancient Greek tragedy. I learned modern Greek from Cretan workmen, when I came as a PhD student to the British School at Athens, and they – wonderfully – invited me to work on an excavation at Knossos and that was the beginning of a lifelong relationship with Greece.

Last year you went back to Knossos to write poems on snake goddesses. Why?

A team of archaeologists, including Nicoletta Momigliano, author of Search of the Labyrinth: The Cultural Legacy of Minoan Crete, commissioned me to do them! You can watch a live streamed event, on the project around the snake goddesses at Oxford on 12th June.

The poems have now been translated by a wonderful Cretan singer- songwriter Kalia Baklitzanaki, and I hope we shall do them in Greek at some point in Heraklion next year.

You come from this enormous clan of high achievers – from the doctor who attended Queen Victoria on her death bed to your beloved late cousin the sculptor Phyllida Barlow. Have you been helped or hindered in your own work by this sense of family achievement.

I think if I had been a scientist, it would have been difficult, but as it was, it was fun and I loved working on Darwin. One person who influenced me very much was my granny Nora Barlow, Darwin’s granddaughter and first editor.

But I think a great theme of your work is collaboration – with musicians, writers, artists, and thinkers. You are clearly comfortable with brilliant people.

Like you, Ian! I loved working with a string quartet for my Beethoven book, Beethoven Variations, and with a Syrian artist Issam Kourbaj for an installation, Dark Water Burning World, honouring the Syrian refugees to Lesbos in 2015 and the Lesbos islanders who welcomed them.

You are the most Philhellene English poet since Byron. Why do we love Greece so much?

The combination of ancient myth and everyday life! all the textures of language, land, stone, memory – and Greek light.

A major element of your work is human and animal migration. You once wrote: ‘Home is where you start from, but where is a swallow’s real home? And what does ‘native’ mean if the English Oak is an immigrant from Spain?’

Yes – migration has been an important part of my work for fifteen years. My book We are all from Somewhere Else has been translated this year into Italian. Italy, like Greece, has been on the forefront of desperate journeys from asylum seekers. The overall message was that migration was a natural phenomenon, in the body and the world as well as human populations. It is part of the way every system protects itself, whether in the body or the world. I moved from the migration of cells, in the body, to tree migration, birds and animals, and then historically, to people. I ended with the idea of the migration of souls.

The book moves through the science and history towards migration today in a rather dolphin-like progression between poems and prose meditations – on home, identity, how you find the way, do you go alone or in a group? A very thoughtful review in the Guardian, by Miriam Gamble of the first editon of the book, titled The Mara Crossing, suggested that it also reflects on how poetry operates: to weigh the implications of how art acts on the “real”’.

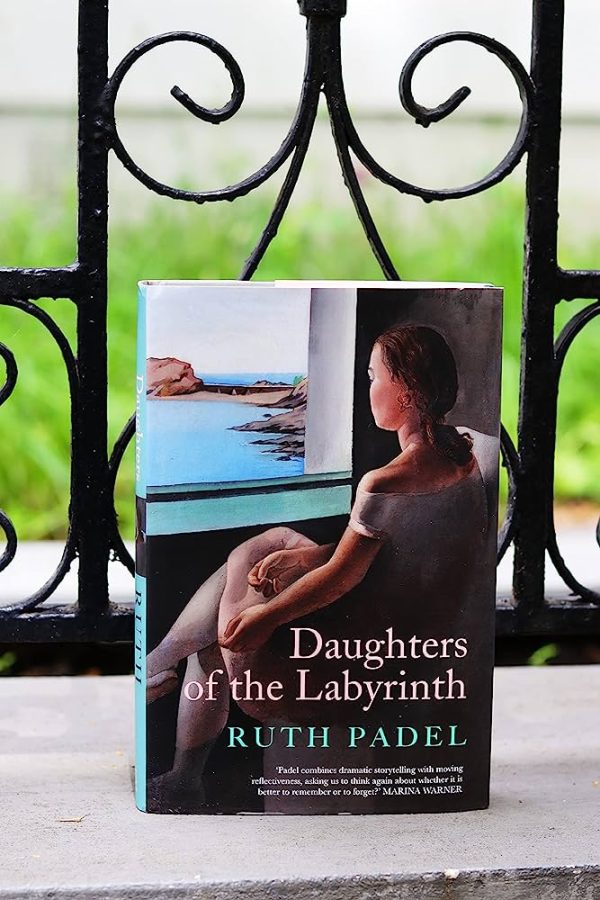

You worked for ten years on the novel Daughters of the Labyrinth. Tell us how that came about.

The novel is set in London and Crete 2019-20, but also looks back to the Second World War. I have lived in Crete on and off since 1970, but it took me till now, over the last ten years, to find the right way to write about a place that has been so important throughout my life – through a story which centres on the last synagogue of Crete, the Etz Hayyim synagogue in Chania.

The book is about love, loss, family, belonging and identity – about parents and children, memory and painting. I wanted to explore the hold of the past on the present, and the uncertainty we all have about what lies beneath the surface of your life. It came about by my meeting Nikos Stavroulakis, a remarkable teacher and the person who rescued the little synagogue, which was once a Venetian church. He told me a lot of stories, and I also got to know the really wonderful staff, historians, librarians and guides, at the synagogue, who are carrying on his work.

We have talked about the need for connectivity. The tragedy of the Jews of Chania was that they were disconnected from the wider world until it swallowed them.

I am not Jewish but was very moved by the history of the nearly forgotten and very ancient civilization of the Jews of Crete. They had an uncanny parallel to the lost civilisation of the Minoans. I have a feeling that the richer, well-connected Jews were able to leave and hide. The ones who were left were not so fortunate, But, that said, a photo recently turned up showing the rabbi of the synagogue with the German officers, socially, at the funeral of the previous German consul of Chania, just a month before the Jews were arrested, at the end of May 1944. Which suggests that no one had any idea what they were planning.

The role of art is to imagine ourselves into other lives but there are clearly huge sensitivities in writing a novel about the Holocaust if you are not Jewish. And I think that a large part of your achievement in this book, is that for all the wild freedom of your language, you are endlessly respectful.

Thank you! That is partly due to my Jewish writer friends who advised me, but above all to Nikos Stavroulakis – his cookbooks, his service booklets – and his conversation when he was alive, were full of the rituals and spiritual explanations for them. I was very pleased that the Jewish Chronicle in the UK said the book felt utterly authentic! I was worried, of course, not being Jewish myself. But I had lived in and out of Crete for so many decades, very close to some Cretan families, that I felt, I could at least try.

There is a lot of light as well as dark in this book – it is also about recovering memory and identity and being an artist.

Yes, I asked a lot of artist friends too, how it feels to paint and draw. The novel opens as Brexit looms in the UK and Greece is grappling with austerity and the refugee crisis. I present it as a land of mass tourism and ancient myth, where Europe’s oldest civilisation was long ago buried by the tsunami, but underneath lie folk legends of revenants and demons and an unnerving silence about more recent history.

The narrator is Ri, a successful artist, Cretan born, but who has worked in London all her life. When her English husband dies, she turns to her roots on Crete, only to discover they are not what she thought. Unearthing her parents’ stories transforms her relationship to her family, her country and herself.

The book looks back to resistance to the German occupation, with echoes of earlier risings against Turkish rule but is also a very contemporary story. As lockdown and coronavirus transform life across the globe. We see an artist who has lived by seeing, discover how very much she has not seen – and that she carries in herself the shade of someone she never heard of. She has to see herself newly, and paint from a different self.

You have followed Charles Darwin in distant journeying, especially to India to record the fate of tigers and, in your next book, elephants. Whereas Darwin was revealing the riches of evolution, you are warning of the dangers of extinction. Given the state of the planet how do we keep from despairing if we can’t be poets?

One step at a time! You do what you can. And be as aware as you can. I always think of nature first.

When I was researching for my conservation-based memoir, Tigers in Red Weather, I realized as I was kayaking rather fearfully down a jungle river in Laos, that while my great-great-grandfather’s journey, through similar terrain but on a different continent, resulted in the understanding of how species came to be, my own journey was a quest to understand how species go extinct.

And where next?

I want to explore Prometheus’s Mountain, Mount Kazbek, in Georgia… I have always been fascinated by the Prometheus story. In ancient Greece, fire was stolen by Prometheus, whose punishment by Zeus, ruler of the gods, was worse than a scorch-mark and has mesmerised the imagination of philosophers, painters, and poets ever since. Prometheus is the archetypal figure of revolutionary defiance, chained to a rock with an eagle eating his liver, which regenerates only to be eaten again the next day. ‘Fire’ is also ‘life’. In one story, Prometheus not only gave human beings fire, and therefore civilisation, but created them.

Ruth Padel is an award-winning British poet, author of twelve acclaimed poetry collections, a first novel set mainly in the jungles of India, an eclectic range of non-fiction from wild tiger conservation to madness in tragedy and the influence of Greek myth on rock music! Her poems have appeared in the New York Review of Books, London Review of Books, The New Yorker, The White Review, Times Literary Supplement, The Guardian and elsewhere. She started out as a classicist at Oxford, has lived in Crete on and off since she was a student and visits regularly, and she is the only person to be a Fellow of both The Royal Society of Literature and of the Zoological Society of London. She lives in London, where she teaches poetry at King’s College. www.ruthpadel.com

Daughters of the Labyrinth, (Little, Brown Book Group) is available in English at all leading bookstores and will be published in Greek by Potamos in September 2023.

Ian Collins is the award-winning writer of John Craxton: A Life of Gifts, (Yale University Press), published in Greek by Patakis, and in Turkish by Yapı Kredi Publications. He curated exhibitions on John Craxton’s works at the Benaki Museum in Athens, and in Chania in 2022. John Craxton: Drawn To Light is currently on at the Meşher, Istanbul’s leading multidisciplinary art space until 23 July 2023.

Leave your comments ...