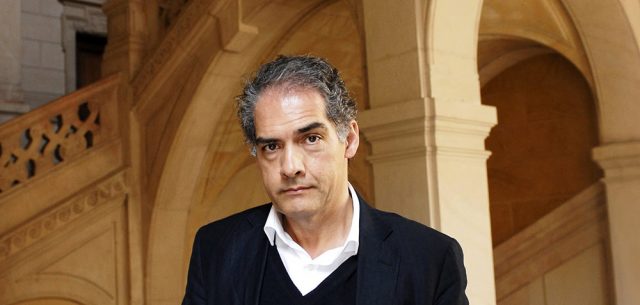

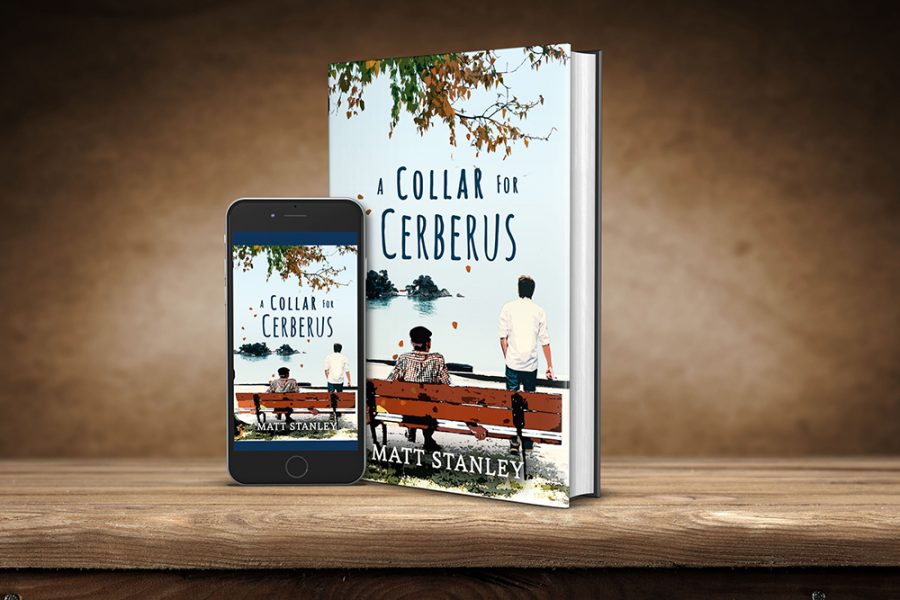

A Literary Labour of Love

Matt Stanley, who penned three crime thrillers under the pseudonym James McCreet, writes his tenth book, A Collar for Cerebrus, under his real name, in a style far-removed from the blood and gore of his Victorian mysteries. In a long, candid interview with Sudha Nair-Iliades, he confesses that this insightful opus is an ode to his beloved Greece, where he learned ‘to love and live life.’

A Collar for Cerebrus starts off with a stern warning: “Never meet your heroes…they’re just conduits for something purer and less real.” That sets the tone for a reflective book, admittedly based on the author, Matt Stanley’s personal journey of self-discovery. Set in Greece, where Stanley spent a few years, the book is dotted with references to places, people and experiences that come alive with his spot-on observations and evocative references.

The allusion to Cerebrus, the three-headed hound of the netherworld is, we presume, a metaphor for German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer’s bleak worldview – a world in a constant state of unhappiness driven by continually dissatisfied people. It prompts the reader to probe a few fundamental existential issues: an exploration of how we live, the decisions we make and what really matters to us.

You’ve written books before under the pseudonym James McCreet. Why did you feel the need to write under a different name and what prompted you to switch back?

I never wanted to be famous or recognized. It was always more important to me that the books spoke for themselves, so a pseudonym gave me that anonymity. Also, I was aware that my early books were ‘apprentice works’ – I was still learning the craft. With Cerberus, I’ve written the best book of my life (so far) and I finally felt it was something I could put my real name on.

Your crime fiction has been described as ‘suitably grisly and lurid, with tremendous style and wit.’ What drew you to crime writing?

I wrote a Master’s thesis on the development of detective fiction, starting with Edgar Allan Poe. It seemed a shame to waste all the good research I’d done, so I used it for my crime series.

What is it about good old-fashioned Victorian murder mysteries that make for such compelling reading?

A crime is a ready-made story. It has victims and heroes and a development and a motive. In fact, the birth of the genre was in the sensational newspaper stories that glorified the grisly details of metropolitan murders. The Victorian city is the forerunner of our modern cities: dirty, dangerous, unknown. Without phones or Internet or computers, investigations were more difficult and crime was a horror lurking in every gas-lit street.

For A Collar For Cerebrus, you switched genres from crime to literary fiction. Why? Isn’t it risky for a writer to move away from a successful tried-and-tested formula to plunge into unchartered waters? How was writing this novel set in Greece different to your other novels?

Risky, sure – but writing is about risk if you want to improve. I believe that a writer always needs to push boundaries and work at the limit of their capability. A series is relatively easy to write once you have the characters and location.

Cerberus was different and special because it represented uncharted waters. I was travelling without a compass or a map – only a sense that what I wanted to say was important, and that my style needed to grow. This Greek novel has more of me in it than the others. It goes deeper than story.

Strangely, it was also easier to write. Perhaps this was because there was so much I wanted to say through the characters and because my passion for the country was so strong. It was a world that I still carry inside me, whereas Victorian London was always a product of extensive research.

Matt Stanley

Tell us a bit about A Collar for Cerebrus. It is a more reflective book – an exploration of how we live, the decisions we make and what really matters to us as the narrator takes a journey through iconic Greece. Do you think that Greeks are better qualified at cracking the code or at least probing the source of true happiness?

You only have to read Homer or the Greek philosophers to find many of the questions we ask about life and happiness have already been answered. I find the origins of storytelling in Homer and in the Greek myths, Greek drama, Greek history.

My time in Greece showed me that the Greeks live for pleasure – to eat, to drink, to dance, to swim, to make love . . . to live in the moment. It’s a sensual and sensuous life. That’s why I felt my character Bastounis had to be a Greek.

The book also has origins in journals I kept while living in Nafplio, Grevena and Cephalonia. I was more alive in those days and appreciated life more. Somewhere over the years I forgot how to love and live life. Work and routine took over. This book was an exploration of how we forget and how we might remember the pleasures of life and what it’s worth.

The book is littered with references to the twelve labours of Iracles (Hercules) and to Cerberus, the three-headed Hound of Hades whose job it was to stop the dead from escaping the underworld. To what extent is the book a modern take on the old myth? Does a collared Cerebrus mean that lost souls can break free, and live again?

The Greek myths offer us eternal story types that are constantly being retold. I was influenced by the Odyssey and by Hercules’ labours as classic narrative forms. The update is in the author Irakles offering his young assistant twelve challenges on how to live a fuller life. As with the original challenges, there will be monsters to kill and obstacles to overcome. Life is full of such challenges and choices we have to make: to avoid what frightens us, or face the fear and grow.

I wouldn’t like to say too clearly what the title signifies because it’s mentioned at the end of the book. However, there’s a question about whether Cerberus was keeping people inside the underworld or preventing them from entering unofficially. Hercules was one of the heroes (along with Orpheus and Odysseus) who entered Hades on a mission.

You’ve been quoted as saying that “No amount of reading can create the same impression as standing in the footsteps of your characters.” Was Irakles Bastounis modeled on a living character?

To some extent, all characters are aspects of the author and the author’s life experience. Bastounis is based on many old Greek men I met, but also on characters from literature. Many of his opinions are my opinions. All of his language is my language. Ultimately, the two main characters are distinct parts of myself: me as a young man and me twenty years later.

It’s always interesting, when travelling, to compare different models of masculinity and what makes a man a man. I remember being impressed by the old men in Greek villages: well dressed in old clothes and with a quiet dignity that also showed their strength. I shook hands with a 90-year-old farmer in Arcadia and felt that my hand would be destroyed for life.

My original quote about standing in the footsteps was about researching locations, so perhaps much of the truth in Bastounis comes from me having visited the places mentioned in the book and my feelings while I was there. When he describes Tiryns or Delphi or Olympia, he is describing my thoughts.

You’ve lived and worked in Greece for three years and your passion for Greece comes through the pages of this book. How, if at all, has Greece changed since then?

I was last in Greece in 2009. It was a sadder place and I know that many people are still struggling. I still dream about returning to visit the sites that inspired me, but I am also finding inspiration in other places. I remind myself that when Odysseus finally arrived home in Ithaca, he didn’t have the urge to travel for a long time!

Are you considering a sequel to A Collar for Cerebrus?

Depending on the success of Cerberus, I have ideas for a sequel in which the young man returns after twenty years, or a prequel in which we trace the life of Bastounis up to the moment when we meet him in his village. Generally, though, I prefer to do something totally new to test my abilities.

Could you name a quintessentially Greek experience that stood out during your stay / travels here? Any memorable meals at a restaurant or under-the radar destinations you’d recommend?

What a fantastic question! There were so many experiences. I remember eating a fantastic fasolada at Mount Athos . . . sitting alone in the ruined church atop Monemvasia as the sun went down . . . eating xtapodia krasato by the sea in Gytheio . . . drinking tea with a blind monk at Meteora . . . gorging myself on bougatsa in Thessaloniki . . . drinking ouzo in the bay of Vathy in Ithaca . . . spending a cold New Year’s Eve on the lake island in Ioannina . . . walking the Diakopto-Kalavrita railway route with a picnic . . . eating Metsovo smoked cheese by a waterfall in a canyon near Konitsa . . . But if I had to choose a Greek restaurant to eat my final meal, it would be Mezedopoleio Noulis in Nafplio. It was like a second home when I lived there.

The book takes the reader through some of Greece’s most iconic sites and a lot of traditional Greek dishes.Why is there such a focus on food in the book?

I often remind people that the English have no phrase for kali orexi or bon apetit or buon gusto or buen provecho! Many Mediterranean countries have a far more developed food culture, in which eating has its own special rituals. I always used to love eating mezedhes, or taking an hour (or more) to enjoy a cold frappe by the sea.

I remember eating cherries or figs or oranges straight from the trees. A few times, I went fishing for octopus and caught them by hand, prepared them and grilled them. The flavours of Greece stay with me now.

The book has things to say about religion and your characters spend some time at the Holy Mountain. What was your experience of Orthodoxy in Greece?

I visited a lot of monasteries and churches, ruined and active. I spent time talking to monks and priests. Regardless of what I might believe, I loved the art and traditions of the Church, and the part it has played in Greek history. There’s a sense of mystery and beauty in Orthodoxy that is irresistible to a writer, and my experience with the holy men of Greece was always (with one very weird exception) very open-minded and interesting.

Athos was a strange place for me – a step back into history. I was there only three days but the time is still vivid in my mind. It’s the kind of place that should exist only in books or the imagination, but there it is in its own isolated reality, a magical place.

A Collar for Cerebrus by Matt Stanley is published by Thistle Publishing, UK. The book is available on Amazon and at leading bookstores. www.thistlepublishing.co.uk.