Leonard Cohen’s Greek destiny: It was the promise of a suntan that brought him to Hydra

Who knew that a random conversation with a bank teller on a dreary, dank September afternoon in London would have such a profound impact on a young writer’s destiny? A superficial exchange about the clerk’s unusually dark tan led to Cohen hopping on a plane to Athens and heading out to Hydra. Hydra promised the life Cohen had craved: spare rooms, the empty page, eros after dark. He found his muse and the love of his life here. This was where he gave his first concert and where, almost exactly to the date, 60 years ago, he bought a whitewashed house of his own, now one of the most visited sites on the island, by the legions of Cohen fans who descend on the island to pay homage to the late Canadian songwriter.

Hydriots leaving flowers in front of Cohen’s home in November 2016. Photograph: Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP /Getty Images

The story of Cohen on Hydra in the 1960s has become central to his personal myth because it is seen as a crucial time of existential and sexual freedom, intellectual liberation and creative solidarity. Those formative years on Hydra were influential in shaping his sense of self and career.

For Cohen, there was something mythical and primitive about Hydra. Cohen initially rented a place for fourteen dollars a month. Eventually, on September 27, 1960, six days after his twenty-sixth birthday, using a $1,500 bequest from his grandmother, he purchased an old stone house without running water, plumbing or electricity. His friend Demetri Gassoumis stepped in to finalise the deal. Cohen, who at the time considered himself a writer rather than a musician, worked on his poetry and novels in the garden, swam in the afternoons, and met up with Australian writers George Johnston and Charmian Clift at one of the several waterfront bars.

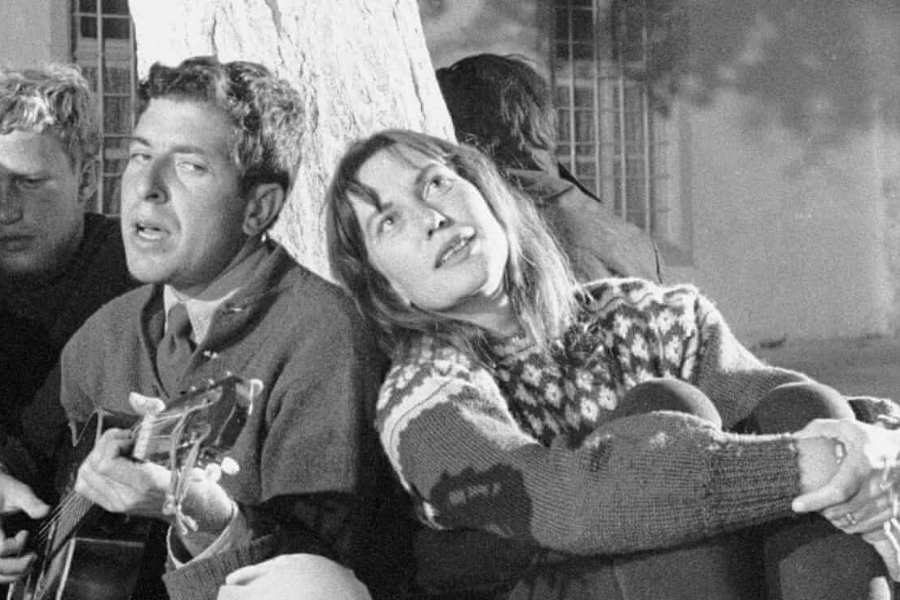

An inspiration: Leonard Cohen with Charmian Clift, Hydra, 1960. Photograph: James Burke/LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Leonard Cohen learned Greek within months of arriving on Hydra. Hydra was where he first performed in front of his friends in the shaded courtyard of the Douskos family-run Xeri Elia taverna and graduated to singing at the Katsikas bar-cum-grocery store on the waterfront on ‘most drunken nights.’ Both these haunts were described as ‘incubators’ by the budding songwriter. Ten years later, Cohen was performing in front of 600,000 fans on another island, the Isle of Wight.

Cohen said of his decision to buy the house, according to his Canadian-American biographer, Ira B Nadel. “Having this house makes cities less frightening. I can always come back and get by. But I don’t want to lose contact with the metropolitan experience. The years are flying past and we all waste so much time wondering if we dare to do this or that. The thing is to leap, to try, to take a chance.”

Cohen described the 200-year-old, 5-room house, split across three levels to his mother as “a spot where he could recollect in tranquility.” During roughly seven years on Hydra, he wrote a controversial poetry collection titled Flowers for Hitler; his first novel, The Favourite Game; and a book about religion and sexuality called Beautiful Losers. Here he began to crystallize the wisdom of some of his best poetry, writing and songs, where the music of Greece entered his soul, evoking earlier memories and melodies, combining with them to suggest a new style, a new mystique.

In an interview with David Remnick of The New Yorker shortly before he passed away in 2016, Cohen acknowledged that Hydra gave him ‘the life he craved for.’ It also gave him the love of his life, Marianne Ihlen, a Norwegian beauty who inspired two of his famous songs, “Bird on the Wire” and “So long, Marianne”.

Marianne Ihlen with Leonard Cohen and Axel Jensen Jr.

And it was here, that he met Marianne, a young woman of great beauty, high intelligence, deep sympathy and fun. The gods had drawn them together, and together for 10 years or so they would make music, exploring the world and themselves, unharried by outside pressures, responding only to the more meaningful pressures of life and love. Ilhen and Cohen both died in 2016, four months apart from each other.

Cohen wrote unblinkingly on how singular and enduring his experience of Hydra was:

“I could not slip away

without telling you

that I died in Greece

was buried in that

place where the donkey

is tethered to the olive tree

I will always be there.”

In recognition of the island’s profound influence on one of the finest songwriters of the last century, Hydra honoured Cohen on his 80th birthday with a stone bench overlooking the Aegean. A street has been renamed in his honour too. Leonard Cohen responded with gratitude: “Dear friends, thank you for the countless times you have lifted my spirit, thank you for the comfort and encouragement. Love and blessings, Leonard.