Memories of Easters Past

Few writers evoke the intense emotion and vivid imagery of Easter in Greece as Sofka Zinovieff in her memoir, Eurydice Street, A Place in Athens. An extract from her book that so poignantly captures the glorious paradoxes and rich traditions of Greek Easter.

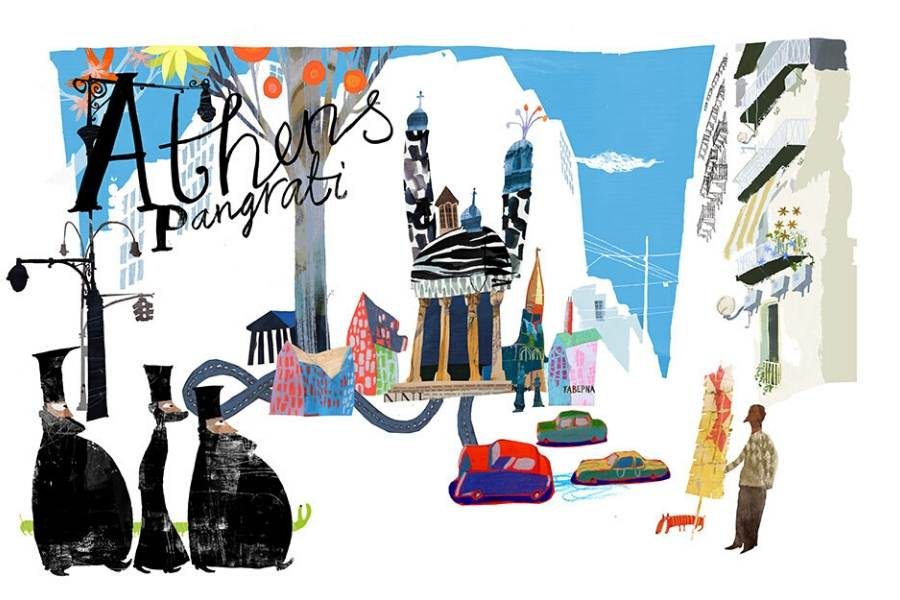

Few would dispute that Easter celebrations are the most intensely beautiful and emotional events in the Greek calendar. Fasting, feasting, grieving and joyousness all combine in the spring-time festival, which is far more significant than Christmas, New Year or the August holiday. Also known as Lambri (radiant or glorious), Easter is a time when most people return to their village or island to join their families and the capital is deserted by over a million people. Given that many shops and restaurants also close for days on end, the idea of spending Easter in Athens may sound bizarre – the loser’s choice. In fact, this time of year is the ideal opportunity for the visitor or the resident to enjoy the city at its most appealing: good weather (not too hot), no crowds, few cars, and an increased sense of local community.

Even in the over-built cement city you cannot ignore the unstoppable energy of new life: flowers and greenery thrust their way up out of any available piece of earth; urban streets are scented with bitter orange.

Hormonal cats yowl on the roof tiles; and misty-eyed lovers are suddenly on every park bench. After the darkness, cold and scarcity of winter comes light, warmth, abundance; the renewal of life itself. Not everyone fasts during the forty days of Lent, though the fact that Greek MacDonalds offer special nistisima (fasting foods) like fried onion rings is an indication of public demand. During ‘Great Week’, leading up to Easter Sunday, there are many more who adhere to the ascetic discipline and avoid meat, fish and dairy products.

Easter procession in the city. Image: Shutterstock

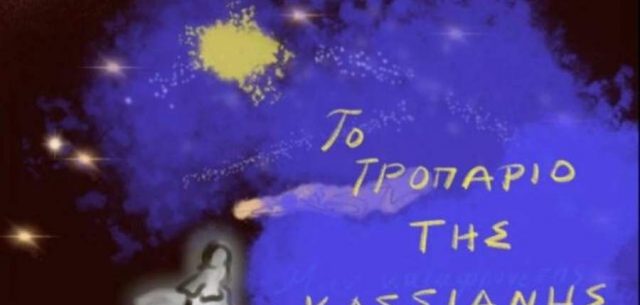

By Maundy Thursday, most people are in the mood, which is one of emotional vulnerability and sadness, exacerbated by physical weakness from fasting. A day of symbolic death, it is characterised by the colour red: eggs are dyed crimson for the paschal table; communion (Christ’s blood) is taken; and traditionally, a red cloth is hung in the window for protection. Scarlet poppies bloom over the roadsides and slaughterhouses and back yards run red with lambs’ blood as they are slaughtered in preparation for Sunday. Churches throughout the city are decorated for mourning: purple silken rosettes are hung and, after the evening service, women bring flowers for the preparation of the epitaphios – Christ’s bier.

On Good Friday, shops and offices are closed, and the city is quiet, but for the slow tolling of church bells. The anniversary of Christ’s descent from the cross is a time of national mourning, and it is still normal to adhere to full fasting (even olive oil is forbidden). In the evening, each parish has its own service and procession of the epitaphios. ‘Mourners’ queue up to kiss the representation of Christ – a gilded cloth lain on the flower-covered bier, much as they would at a funeral of a loved one.

Reminded of their own losses, people weep for Jesus and for themselves.

The subsequent slow march from the church around neighbouring streets is a moving affair, as the candle-lit procession follows Christ’s ‘coffin’. Those who prefer a larger, archetypically metropolitan version (in the presence of the Archbishop, politicians and TV cameras) can attend the Cathedral and follow the procession up to Syntagma (Constitution) Square. It is also enjoyable to walk around Plaka, visiting different churches, before choosing a favourite. Saturday is already a happier day, when people prepare for the celebrations to come.

The sights and smells of a Greek Easter

By the evening, everybody is dressed in their finest, and ready for the ‘resurrection.’ Even in the city, churches are packed, and while many are loyal to their local church, others visit more picturesque neighbourhoods such as Psyrri or Plaka. Almost everyone goes to the Easter Saturday service – from the youngest to the oldest, and from the devout and dutiful to dedicated atheists and communists. Children clutch their lambades (specially decorated candles, bearing small sweets and toys), and wear shiny new shoes – traditional gifts from the godparents. Inside the church, the tension mounts as people crowd in, listening to the ancient Byzantine hymns, which have not changed for centuries on end. The air smells of incense, perfumes, hair spray, hot wax. Just before midnight, the lights go off, and then the priests emerge from the sanctuary with a flame – Christ’s resurrection–from which everyone lights their candles, kissing one another and wishing ‘Christos anesti!’ (Christ is risen) and replying ‘Alithos anesti!’ (Indeed he is risen).

This is not just any fire. Quite apart from the symbolism, it has probably actually been lit directly from a flame brought that day from Jerusalem by aeroplane – brought forth from the Holy Sepulchre by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch (often struggling to get it before his Armenian counterpart). Once in Athens, it is driven from the airport directly to the seventeenth century church of Saints Anagyroi (the Holy Penniless) in Plaka. And from there it is distributed around many of Greece’s churches (using boats, cars, planes and even helicopters).

As soon as midnight has struck, bells chime, fire crackers and fireworks go off with deafening bangs across the country, and ships sound their horns.

The Church’s job has been done, and the vast majority of people leave quickly to devout themselves to matters of the body rather than the spirit.

The first thing is to head off hungrily for some food after all the fasting. Mayiritsa (soup made from the paschal lamb’s intestines) is the traditional dinner, which is normally eaten at home, but can also be found at tavernas. Also present are red hardboiled eggs, which are taken and knocked against each other to find the “champion.”

Christos Anesti …

The late night dinner is usually followed by early morning preparations for the Easter feast, but nobody seems to mind the lack of sleep; it is impossible to suppress the exuberance. There is no question about what to eat; it is always lamb, spit- roasted over charcoal. And the idea is to over-indulge – to eat too much, to drink, dance and feel the sensuous pleasures of life returned.

If you haven’t got a Greek family, you’d be well advised to adopt one for the duration, as tavernas do what they can (Plaka is probably the safest bet), but nothing compares with the home-made version. All over the city, people are out on terraces, in backyards, and even with portable barbeques at the beach, roasting their lambs and nibbling bits of kokoretsi (lambs’ intestines and offal wrapped on a long skewer and barbequed). Popular Greek songs are played at full volume, wine flows, and the dancing begins, as the whole country enjoys its favourite day of the year.

Athenian Easter may be less intimate and community-oriented than in a village, but its highs and lows are just as powerful. The city is perfectly able to offer us regeneration and a sense of life-force, as we witness the eternally optimistic cycle of winter to summer, darkness to light and death to life.

Alethos Anesti

Sofka Zinovieff is the author of Putney, The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother and Me, Eurydice Street: A Place in Athens, and Red Princess: A Revolutionary Life and The House on Paradise Street. www.sofkazinovieff.com