A Greek Homecoming

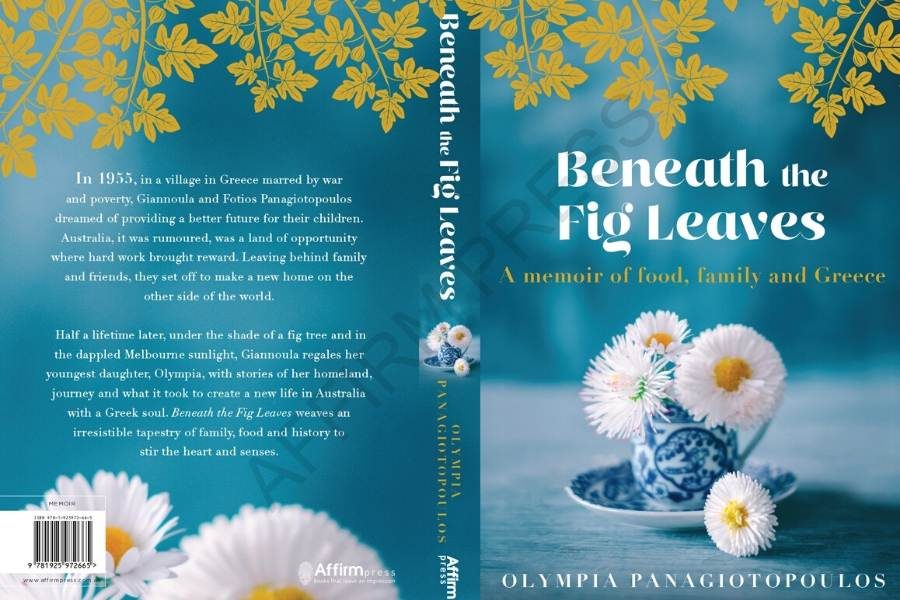

Olympia Panagiotopoulos’ poignant story will resonate with anyone who has left home on an immigrant’s journey, «a life caught between a memory and a dream». In Beneath the Fig Leaves, «the comforting sizzle of onion and garlic in hot oil, the fresh, clean scent of a newly picked lemon, the strong earthiness of thyme» infuses the cultural and culinary adventure she embarks on with her mother in her native Messinia.

In the village of Chrysochori, Messinia, more than fifty years ago, my mother Giannoula and my father Fotios dreamed of a different way of life for their family. Australia, it was rumoured, was a land of opportunity where hard work brought reward. Farewelling beloved family and friends, they set off to make a new home on the other side of the world.

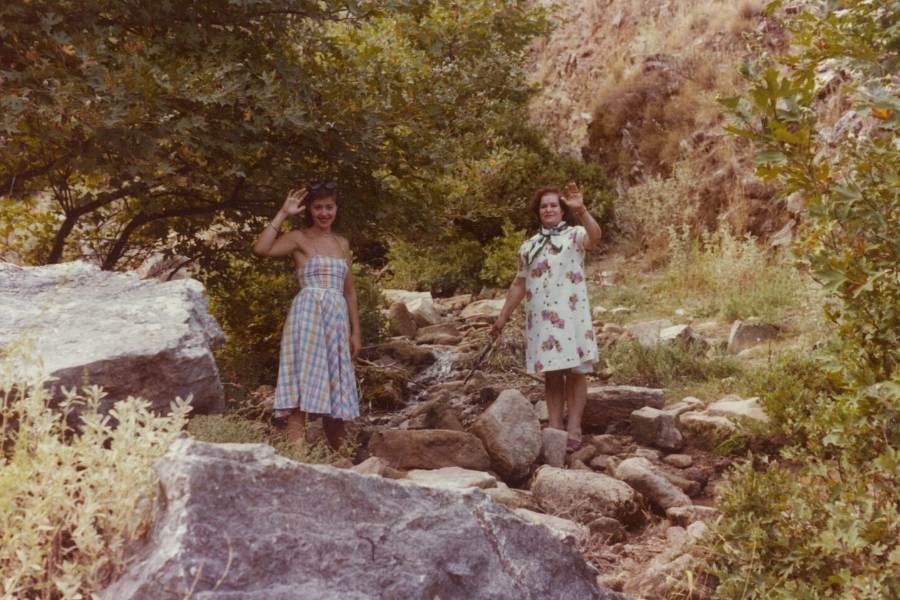

The momentous occasion of Fotios and Giannoula’s return to Chrysochori in August 1981 after twenty-six years in Australia.

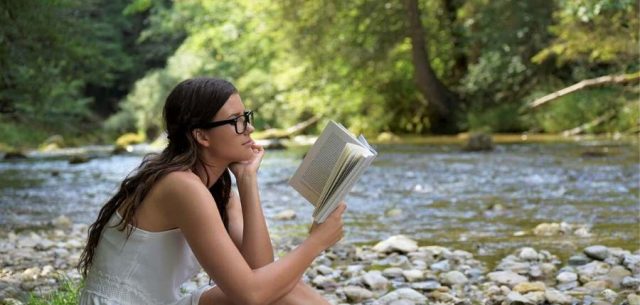

Half a lifetime later, under the shade of a fig tree in my mother’s garden in Melbourne, I was moved to collect and document the stories that she shared with me: tales from her homeland, the long journey south, and what it took for my parents to make Australian life their own. I had always taken an interest in knowing my family’s history – I was the only Australian-born child in the family, the only sibling to not have wandered the fields and mountains of Chrysochori as a child. The village and my parents’ life there held a deep fascination for me. The more I learned, the more I wanted to know.

In the spring of 2009, my mother and I embarked on a cultural and culinary adventure as Beneath the Fig Leaves came to life. Against a backdrop of mornings in the garden and afternoons in the kitchen preparing generations-old recipes, I was reminded of the beauty and importance of taking the time – busy though we may all be – to enjoy and appreciate life’s simple pleasures: the comforting sizzle of onion and garlic in hot oil, the fresh, clean scent of a newly picked lemon, the strong earthiness of thyme. And most importantly of all, a mother’s love.

Village girls. Mother and I on the mountain at Karasafka. Mother reminisced about her summer garden and said she wanted to climb up to pick rígani like she did when she was young.

A powerful exploration of the ties that bind, Beneath the Fig Leaves is a rich tapestry of family, food and history that stirs the heart and senses.

Excerpts from the book:

On 6 August 1955, Giannoula and her aunt Efterpi were travelling home on horseback from a monastery in the mountains where they had celebrated the feast of Saint Sotirios. They stopped in the town of Dorio, where Giannoula learned from the priest’s wife that their application to Australia had been successful; the health checks and paperwork had been approved and Australia would welcome them. In seventeen days, a ship was departing from Piraeus. But Fotios and Giannoula had to come up with five hundred drachmae per person to complete their application. They had no choice but to sell the field that Giannoula’s father had given them as part of his daughter’s dowry and their donkey, which Fotios saddled up and took to the market. Selling their property heightened their sense of distance, heartache and loss. What if they returned home one day? Would anything that said they had been there remain: a piece of earth, the olive trees, the house?

Life in post-war Greece was hard for my parents, Giannoula and Fotios, pictured here in their immigration photographs.

Giannoula was anxious. She began sorting and organising the family’s belongings, the details of their lives. Australia was a mystery to her: its environment, its people. She had no idea what she would need or what she was about to find. She filled a large bag full of clothes they couldn’t take on their journey and took it down to the village square to give away, setting aside a few items for her aunt Efterpi and her daughter Magdalene, who was blind. Giannoula wished she had more to give; she felt a sense of betrayal knowing that she was moving to a land that would bring her family more, while leaving behind loved ones who had so little.

With just days until their departure, Giannoula and Fotios began their farewells. They held a memorial service for their family members buried in the village cemetery. Their relatives and many villagers attended, and for that Giannoula was grateful. She and Fotios had grown up with these people, had known these faces all of their lives. She was overcome with sadness and knew that many of them shared her fear that it might be the last time they would gather together. After everyone had gone, Giannoula sat by her mother’s grave, offering prayers and gratitude.

Picking plump, ripe figs from my mother’s garden was the highlight of the summer season.

On 19 August, Giannoula and Fotios awoke at four in the morning and gathered the children. It was still dark as Fotios’s nephew, Georgios, loaded their trunks onto two horses. On their journey out of the village, Fotios visited his brother, Giannis, who was distraught and could barely stand. He had fought hard for the family to stay, and Fotios feared the sorrow would consume his brother. Giannoula visited her family home. She held onto her brother Georgios as they cried. Part of her wished that her brother wouldn’t let her go and for a moment she prayed that Australia had changed its mind. Brother and sister promised to write, to be in good health and to remember each other. To never forget the village, the fields or the vineyard. To remember when they were young, when they ate walnuts and drank wine and got up to mischief. They spoke of their mother’s goodness.

‘You are just like her,’ Georgios told Giannoula. ‘Mamá and Yiayiá loved you so much. You will remember, Giannoula? Promise me you will remember it all.’ Georgios smoothed his sister’s hair. ‘God has blessed you, Fotios and the children. He has blessed your journey. May the life you make in Australia be long and may you meet good people.’

‘We will meet again,’ they agreed, ‘with God’s help.’ Neither knew when or if that would be – but that, they didn’t say. The wound of missing and longing and regret had begun.

Giannoula’s father was eighty-two and in bed, sick with grief that his daughter was leaving. She knelt and kissed his feet and then said goodbye. ‘For the last time,’ she whispered to herself, making the sign of the cross.

Giannoula hurried to meet up with her family, running through the village streets. There was silence, but the beat of her heart was resurrecting memories and images of people and places that seemed to lunge at her, grabbing and pulling her back.

Fotios, Giannoula and their children, together with Fotios’s nephew and the loaded-up horses, began their walk to Dorio, where they were to board the train for Athens. For a moment, Giannoula and Fotios stopped and looked back at the village, the olive trees, the roads and the stones; at the ghosts that remained. Fotios picked up a large stone and threw it down hard. ‘Den patáo píso, I won’t step back here!’ he cried out in despair. The village was asleep, but light was already creeping along the church tower. Fotios and Giannoula continued on.

In Athens, they stayed with one of Fotios’s friends from the village who rented a house there, his wife laying out mattresses on the floor for them. It was Giannoula’s first visit to the city. They had three days before they sailed and spent the time finalising the details of their journey. They bought some personal items and an additional wooden trunk for their belongings. For their last meal, Fotios bought a leg of lamb, which they cooked and ate with spaghetti and a large handful of grated myzíthra cheese.

Giannoula looked at each of the children as the family ate, blessing them as she wondered what lay ahead. The twins were eight, their sister, four, and young Andreas, two. Would they remember Chrysochori? This was the immigrant’s journey, a life caught between a memory and a dream.

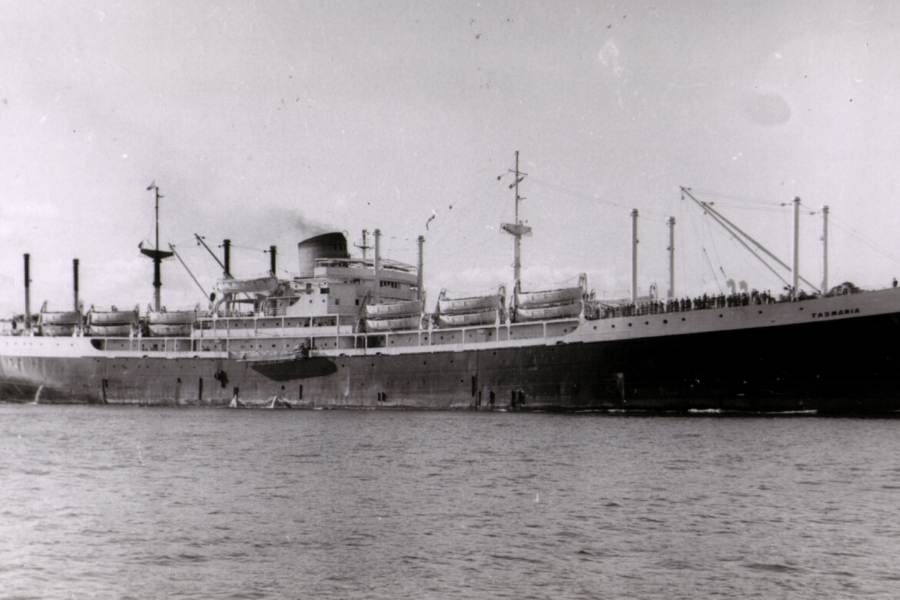

The Tasmania , the ship that carried my parents and siblings to Port Melbourne, Australia in 1955. It was a difficult, month-long journey, but the thought of the prosperous, happy life that awaited my parents in the new country buoyed their spirits. Photograph reproduced with permission from Seaworks Williamstown (Seaworks Foundation.)

Early the next morning, on 23 August, the family boarded the ship that would take them to Australia, the Tasmania. The scene of people crying and clinging to their loved ones only added to their heartache. White handkerchiefs flagged through the crowd as the growling ship pulled away from the dock. ‘Kánte to stavró sas, do your cross,’ Giannoula said, holding onto the children. A chorus of voices rose as passengers and those left behind began singing their anthem of courage and fear. Their voices reverberated through the port, sending ripples across the water, as the Tasmania made its way out into the Aegean and then the Mediterranean Sea, sailing towards Australia.

Beneath the Fig Leaves by Olympia Panagiotopoulos (Affirm Press) is out now.

Insta: olympiapanagiotopoulos, Facebook:@OlympiaPanagiotopoulosAuthor