Gilbert & George: Singing that Familiar Tune

Stephanie Bailey meets Gilbert and George, the prolific British duo flying the flag for art that rises from the multicultural streets of East London.“Art is boring if it doesn’t speak,” says Gilbert Prousch. “We try to make images so powerful people will remember them”.

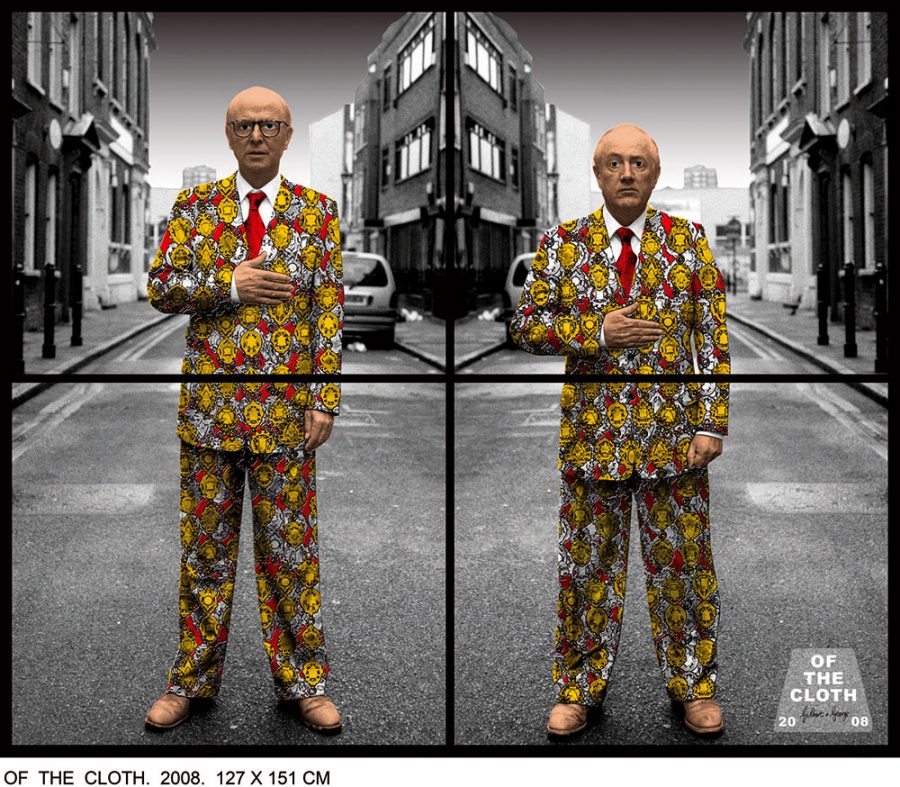

“Our art has always been about death, life, sex, fear, money, race and religion.” So says George Passmore, who makes up one half of notorious artist duo Gilbert and George alongside Gilbert Prousch, in a conversation with scholar Michael Bracewell at the New Benaki Museum on November 18. The talk was a packed-out event held one night before the official opening of their current exhibition at the Bernier-Eliades Gallery, featuring images taken from their latest picture series Jack Freak Pictures. Comprised of 153 images, this is their largest and most commercially successful series in a career that spans almost 40 years.

Earlier that day, I had my own private conversation with the self-defined ‘Living Sculptures’ – British art’s equivalent to Queen Elizabeth II. Wearing trademark tweed suits in colours most would associate with a Constable landscape, meeting the artists – who are always a feature in their work – was a revelatory moment.

In terms of output, Gilbert and George have built an artistic career very much based on the manipulation of their own image. As students in the sculptural department at St.Martin’s School of Art, they launched their artistic careers with a performance entitled, Singing Sculptures, first shown at the Nigel Greenwood Gallery, London in 1970, and subsequently travelled the world. A performance featuring the pair standing on a platform with their faces painted gold singing Flanagan and Allen’s “Underneath the Arches” for eight hours, it introduced the world to walking, talking icons at work.

Best-known for their series of “Pictures”, including the “Dirty Words Pictures”, which documents street life in Thatcher’s Britain, the “Naked Shit Pictures”, images created with urine and faeces, the “Son of a God” pictures that took on the aesthetics of the church in order to comment on its practices, to the “Jack Freak Pictures” today, essentially a series that reflects, relates and in turn, defines the changing face of Britain, they have built a portfolio of work that has mirrored and in part defined Britain and British art.

On their reputation for being artists with a passion for shock tactics contrasted by their conservative exteriors, Passmore says: “So-called intellectuals assume that artists are, by nature, anti-establishment. So they assume we use our work in that way. But we are not critical artists. We approach things head-on.” Needless to say, this is an artistic duo with their fingers firmly on the social pulse – not content with pretty pictures that contain little or no message.

In the “Jack Freak Pictures”, the Union Jack is a common feature, though it is often warped to the point that its colours have changed, or it has become part of a larger pattern that evolves the Christian or Catholic stained glass aesthetic to include often geometric shapes that almost appear Islamic. In a sense, their latest project addresses the idea of nation, nationality, race, religion and belief in a globalised world that was in part created with the help of the British flag – as seen from their vantage point in multi-cultural east London. “It is extraordinary how things have changed in East London; it’s like a little world,” they both note.

Far from being passive participants in the world around them, Prousch admits with obvious pleasure; “We do like to press a lot of buttons,” something anyone familiar with their work is aware of. “That’s the artist’s job,” Passmore continues, and he’s not fooling around. By playing with instantly recognizable motifs and themes that can be interpreted in a plethora of different ways, Gilbert and George are determined to highlight, rethink and – where necessary – ridicule terms, definitions and symbols with a bit of dry humour thrown in for good measure.

“We do this because we have nothing better to do,” says Prousch. “The young ones have to go to the bank and make money – we don’t have to do that, we just feel life; we feel the world differently.”

The humanistic element to their work is very much in tune with their motto, ‘art for all’, which to many, contradicts their well-documented belief that Margaret Thatcher did a lot for British art, which Prousch clarifies with the justification: “Thatcher arranged the free market economy. At that moment you could be rich and you could buy – suddenly not only the state was buying art.” At the Benaki talk the issue came up when a university student questioned them on their political views, only to have Passmore answer, “We are for the individual, not collectivism.”

As such, Gilbert and George have cleared a path that has led them away from the cold, clinical, commercial approach often associated with the Pop art movement and its legacy. Passmore maintains: “We were never part of that big commodity, and we never pushed prices.” Where some artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst run studios along the lines of Warhol’s factory, or a Renaissance workshop, Gilbert and George work to sustain themselves so that they can make art without having to compromise – and are proud of it.

“Art has always involved the rich,” Prousch concedes, “but what we wanted was to be seen by more and more different people – that was our message. Art is boring if it doesn’t speak. We try to make images so powerful people will remember them.” This explains their excitement when discussing their current exhibition, which will move on to be shown in public museums after a tour of private galleries that took them to Berlin, London, Paris, Salzburg, Athens and, next, Naples. The shows will no doubt do just what Gilbert and George love doing most – provoking a strong, mixed reaction, and in turn, a lively debate.

“We feel our real job is to form life,” Passmore says indignantly. “By making pictures, maybe tomorrow will be different – at least that’s the hope anyway.”