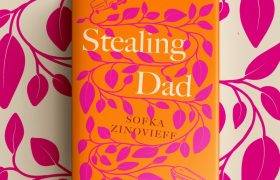

Putney, a modern day Lolita partly set in Greece

Karine Ancellin meets Sofka Zinovieff, whose latest book, Putney, set in Britain and Greece, walks into the uncomfortable centre of the #MeToo storm while questioning the free-spirited interpretation of consent and control in the ‘70s. A compelling novel by Bloomsbury, Putney has received critical acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic.

Putney brilliantly articulates three perspectives within two different time frames, first during the 1970s; adolescent Daphne’s innocent voice accompanies Ralph’s infatuation of her, until she becomes a mother herself. Then, nowadays, Jane, her best friend of old, prompts her to rethink her teenage “love” with the famous British composer, Ralph. Set between London, Athens and the island of Aegina, Sofka Zinovieff’s ability to cleverly express the complexities of her characters stem from her thorough experience of both cultures, as she explains:

“I’ve been very lucky, firstly, having been born in London, with Russian heritage, I already felt a little of an outsider which is a great benefit for a writer. Then, coming to Greece as a student, it was a place that fully resonated with me. I learned about myself as well as learning about the country. Then I also lived in Rome for 5 years and in Moscow for a year and a half. These stays helped give me the ability to come and embed myself somewhere new. Greece is my adopted home, my husband is Greek, my children feel themselves to be Greek, just as much as they are British, if not more. They were born in England but they spent their formative years living here, in Greece. So, as the mother of Greek daughters that is a kind of lovely way to be pulled in and rooted to a place.”

In her timely novel, Putney, Sofka Zinovieff examines the facets of suffering and resilience through a work of fiction that delves into child sexual abuse, as it happened at the time, and as the characters reminisce 40 years on. When our conversation took place this summer, Sofka Zinovieff had just returned from London for her book launch, and Putney had received excellent reviews. Understandably, it offers a subtle and nuanced alternative to the righteous populist generalizations on this delicate contemporary issue. The white and blue hues of Patmos Island modulated our discussion. She revealed how this idea came to her:

“Funnily enough, I had started writing Putney before the #Me Too jamboree movement began, so it wasn’t as a result of that. They came out alongside each other. There was obviously something in the air, in the Zeitgeist. I think partly it was seeing in recent years how many prosecutions there were relating to cases of child sexual abuse in the past, partly it was learning about how many of these are not straightforwardly understood.”

Sofka Zinovieff

Intrigued by Putney’s atmosphere that oscillates between the London spirit of post-sixties creative irreverence of young Daphne’s family, and the contemporary British debate on permissive behaviors, I asked the author if it connected with her own experience: “There was that part of the 1970s culture when anything goes, liberation, flower power, sexual liberation, and the way people just didn’t think about abuse, or what underage sexual relationships meant, in the same way we do now. I can see it because I was brought up in Putney, in that area of London; I was a teenager there, in a milieu very similar to Daphne’s. Putney is not my story, not my family, but I wanted to base the novel physically in an environment that existed and in the area of Putney where I grew up – by the river, with the Railway Bridge. The Bohemian lifestyle is also similar to the family I grew up in.”

The author’s non-committal, non-judgmental tone is the part of her craft that best renders the contradictions and ambiguities contained within the tantalizing question of child sexual abuse:

“I’m very keen on looking at grey areas. I find fascinating to penetrate the mind of the “bad person” and to try find out how he is feeling about this, how is he justifying it, what’s it doing to him. My anthropological training has really helped me with this work. As an anthropologist you have to suspend your judgment and allow for other people’s beliefs and for other people’s way of doing things which may well not be how you like to do things but it is the way they believe is right, so I know that if you look around the world, in some cultures you will see children getting married at that age, you see people having more than one partner, there are different ways of approaching sexuality.

“I’ve come across quite a lot of people who have been fluid in their sexuality. I think that Ralph, cannot be called homosexual, he just has a strong sexual appetite, and he was interested in males as well as females but on the whole, younger males. In the English education system you hear so many stories of boys who have had love affairs or sexual affairs when they are young. Then it can be something that stops completely when they leave school and become involved in women, or it can be a thread running through their lives, there are so many ways, we are quite keen on labeling somebody’s sexuality but throughout much of history it has not had such a clear cut label.”

Putney

If one scrapes the palimpsest of the overlapping stories in Putney the reader can trace the author’s cultural grounding in classical music and literature: “one thread has to do with Innocence and Experience. It’s not by chance that Ralph composes songs based on William Blake’s ‘Songs of Innocence and Experience.’ There is a play around this child who could be nothing but innocence. I am also playing dangerous games of innocence; I am allowing Ralph to portray himself as having had a sort of innocence. Many people in that era allowed themselves to think, “We’re in Love what could be wrong with this?” So, I really wanted to run out the romance. I have Ralph groom the reader, so that the reader is seduced as well. That is why quite a few people find the first part of the book difficult to stomach because there is a lot about Ralph’s feeling of “love,” even though he is grooming and abusing a child, and at the same time we read thirteen year old Daphne’s feelings of “love” even though she has been groomed, and its more the obsession of a young girl, that an older person should not be allowed to act on.”

Aesthetically, I read the descriptions of the skies as echoing Turner’s relation to the elements refracting human vulnerability and wondered if it was a deliberate style in Putney: ‘the Mandarin Clouds’, ‘the Milky Sunshine’, ‘sky turned Graphite grey’, “Yes, from the beginning when Ralph goes for the first time to Barnabas road, it’s cloudy as if the sky had a hangover, so the sky keeps coming back as a somewhat direct reflection or implication on people’s mood, playing with symbolism.”

Since Putney probed such a sensitive issue, I was curious to know if some of its readers, amongst whom the Greeks, imagined she had betrayed them when writing about Greece, but Sofka Zinovieff retorted:

“Funnily enough it hasn’t happened. It was something I was really waiting for when I wrote the ‘The House on Paradise street’ because I understand the sensitivities Greeks often feel when an outsider writes about them, or their history, or their way of life. Greeks often get upset and feel that the outsiders have got it wrong, or that they have been denigrated or that they were portrayed unkindly. So, I was absolutely braced, especially as I tackled the Greek civil war, one of the most sensitive issues. Greeks among themselves, let alone in their relationships to outsiders, have not thrashed that out fully yet. It is very much a work in progress. I would say it is interesting that after national traumas, or in view of Putney, personal traumas, these things are often dealt with much later. These subjects can be too sensitive, for writers as well as for the general public, therefore it takes a sort of settling down of things to be able to recognize what has happened and see it in a slightly cooler light.”

When I spoke to Sofka Zinovieff in July, we were still under the shock of the devastating fires in Greece, so I also wanted to know how she had received the news: “It’s a terrible time and, of course, as with many tragedies, I think it brings up a lot of anger as well as sorrow, because we have to ask all the unpleasant questions. Some people have said that it was biblical, or an act of God. As in London last year when we had the Grenfell tower-block fire, there was a lot of anger, involving who was to blame. Probably there are things that can be improved, people have said lack of planning, defective access, lack of coordination, that sort of thing. Over time, there has been so much suffering. The country hasn’t had time to get back on its feet again, it’s just been one thing after another with war, occupation, dictatorship, famine, fires, of course, the financial crisis, but the crisis is by far the first time Greece in its modern history has been knocked down really low, and had to pull itself up again. Greeks are amazing survivors, they have horrors inflicted on them but they pick themselves up and create life once more.”

Sofka Zinovieff will be in Athens for the launch of Putney at the Athens Centre.

Wednesday September 19th at 7 pm. Athens Centre, Archimidous 48, Athens 116 36