Spy Daughter, Queer Girl: Leslie Absher’s Poignant Memoir

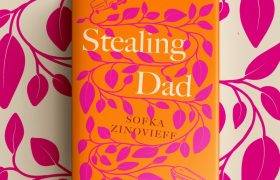

More than a poignant memoir, Spy Daughter, Queer Girl is a thrilling detective story where the stakes are both unique to the child of an intelligence officer and painfully universal. Leslie Absher unravels deep-seated secrets: of her family, her identity, and her father’s role in Greece’s CIA-backed junta. She speaks to Diana Farr Louis on growing up in Greece, and of secrecy being just another member of the family. Throughout childhood, her father’s shadowy government job was ill-defined, her mother’s mental health stayed off limits—even her queer identity remained hidden from her family and unacknowledged by Leslie herself. Published by Latah Books, her absorbing prose draws readers to the shade of plane trees in Greece, to queer discos in Boston, and to tense meals with her aging CIA father. Absher renders a lifetime of hazy, shape-shifting truths in high-definition vibrance.

Ms. Magazine sums it up in a nutshell: “Spy Daughter, Queer Girl is succinctly written, gorgeously rendered, and emotionally illuminating. One could describe it as part memoir, part spy thriller, and part mini-history of being young and gay in the ‘80s.” And you don’t have to be gay, have the slightest connection with any hush-hush activity, or even be female to feel, see and relate to everything that Leslie Absher communicates with such skill and courage.

But what makes Leslie’s book even more fascinating and relevant to readers in Greece is this is where it all begins. And by it, I mean both her story and her father’s. For anyone who knows Greek history, the dates are a clue.

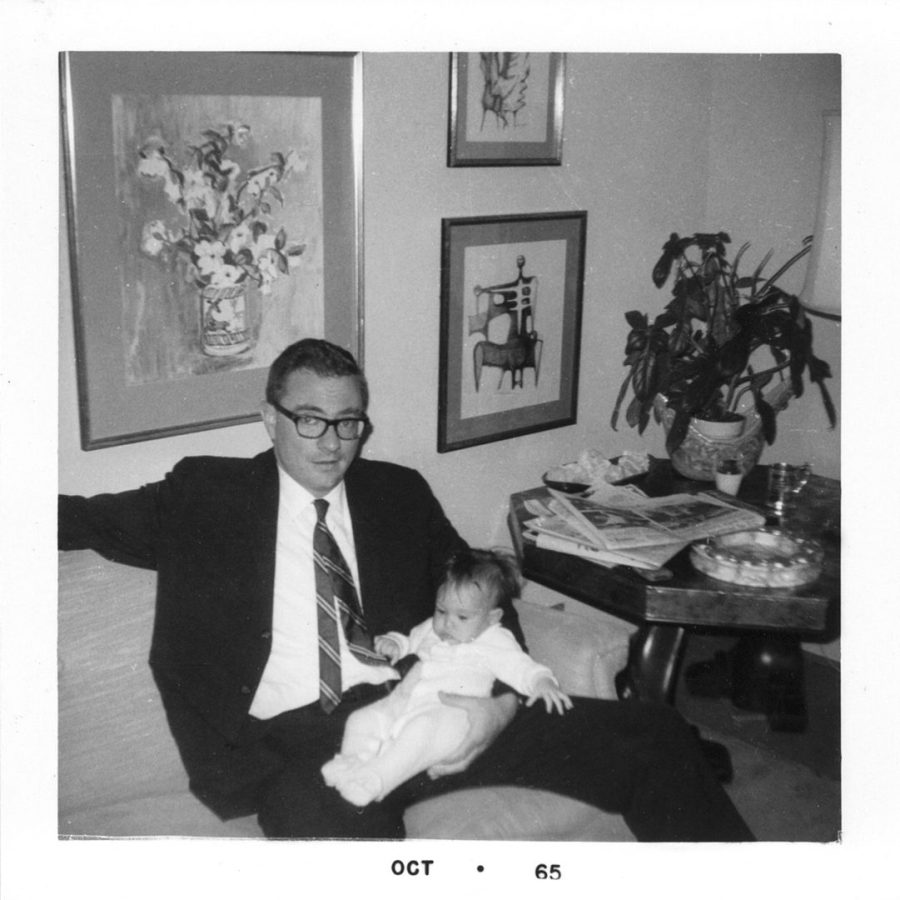

“Greece was my first home,” she told me in a zoom call from her house in California. “I was a baby when we arrived in 1966 and six when we left. We lived in Palio Psychiko and my nanny Anna, a 19-year-old-country girl, taught me the language. With her help, I even learned to read in Greek, before I read in English.”

The warmth, tastes, smells, sounds of Greece became etched in her memory, “And I realized I had to write them down before they became diluted by more recent experiences. Sometimes all it takes to make me realize I’m home again is a whiff of Athens’ exhaust fumes,” Leslie chuckles. “Because I’ve been back so many times, I keep ‘upgrading my software’, but the kernel remains the same.”

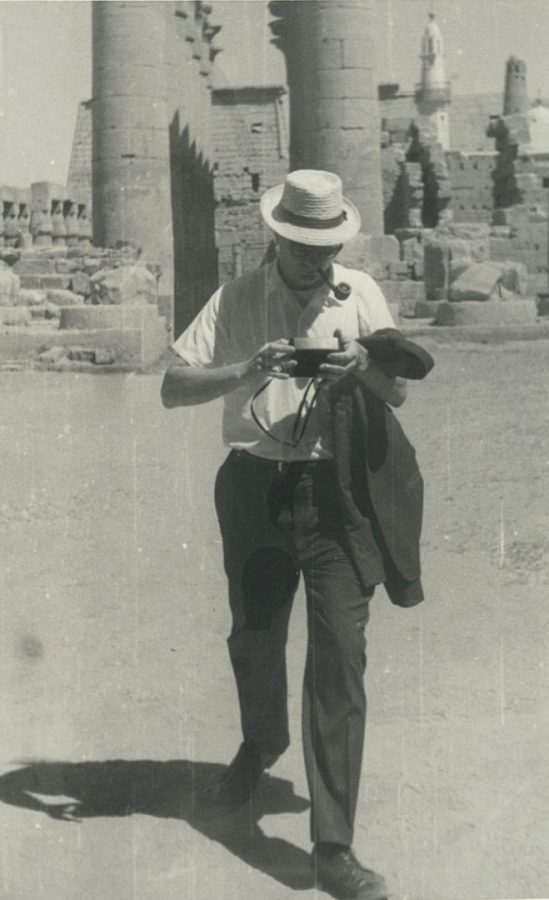

Back in the US, in San Antonio, Texas, the family’s next home, Leslie begins to wonder what her father does for a living. He’s an enigma, not like other dads who talk about their work, bring home stories about the office. First, he tells her he’s in the army but she’s never seen a uniform. Then she overhears a phone conversation when he says he’s in the State Department. He disappears for a while, to Vietnam, she learns later, and her mother, a lively, loving artist, succumbs to depression and then to cancer, when Leslie is in her mid teens. But not before she challenges her husband in the car one day: “Tell your daughters what you do for a living . . . you work for the CIA, don’t you?”

The secret is out. It explains all the moves, the unhappiness, her mother’s illness. But because her father grew up in a Mid-West family where “it was inappropriate to talk,” no discussion follows, dead silence ensued for the rest of the ride, and it was never mentioned again.

But now Leslie knows, and as questions bubble up inside her, she’s also dealing with her own sexuality (her forbidden life), which she hasn’t even truly admitted to herself, and decides to spend a college semester in Greece. By now it’s 1985 and with PASOK decisively elected to a second term, anti-American and anti-CIA posters and slogans greet her. Guilt and shame engulf her as she learns more about the role of the CIA in aiding and abetting the Colonels’ coup in 1967 and the practices that kept them in power.

“I had come to Greece to find myself but the only person waiting here was my father.”

And so it continues, their stories overlapping, silences, estrangement, more and more discoveries in a book that could be called, like Gunter Grass’s, Peeling the Onion. It took Leslie Absher 17 years to process her discoveries, emotions, complicated relationships and write them into this moving, gripping narrative. But as a journalist, she knew writing was the only way she could deal with it, free herself from the “toxicity of secrecy.”

In her quest, she found immense help in Greece by attending several sessions of Amalia Melis’s Aegean Arts Circle writing workshops on Andros (which is where we met). Her first was with Dorothy Allison, author of the wonderful memoir, Bastard out of Carolina, in 2004. Allison told her “to write into your fears,” and when Leslie showed her the first attempt, she replied, “This is not an essay. It’s a book! Her encouragement and belief meant I had to go deeper.”

There by the hotel pool, she had another revealing, spontaneous encounter with none other than Nick Papandreou, who had his own intimate connection with the CIA and the Junta, through his own father, Andreas, the charismatic, controversial politician. Author of a memoir himself, Father Dancing, he would also be a future instructor at one of the five or six workshops Leslie attended.

“The story kept changing as I found out more things, found out more about my father, and started to see things in a more nuanced way, more gray than black and white. Life changes. That’s the thing about memoir. I also had to battle my fear, girding myself to show him the book. Among our basic differences was that I was part of the modern, socially liberal generation hurtling fast into the future, while my father belonged to the past, to a time when most men had no idea how to be emotionally present.”

This book could even be a manual for dealing with grief, the trauma of neglect, shame and deceit, but it is also permeated with love and joy: a relationship that ends in a happy marriage, the fun of being liberated, dancing and marching in Pride parades, and swimming, even in the icy waters of San Francisco Bay – without a wetsuit!

“Water sustains me. It buoys me up. Being in the waves has got me through so much pain. Losing my sister a couple of years ago, my own battle with cancer at 54. I see every journey of hardship as an opportunity to grow out and grow bigger, to expand. I feel that the universe has presented these hardships as a door. Walk through it, and I’ll come out healed. It gives us the resources to move into healing and joy. I came to a more nuanced understanding of the CIA, reconciled with my father, and with myself. It has been a healing process to write this book.”

And now that Leslie Absher has with so much courage, introspection, and penetrating analysis published her multifaceted tale, Spy Daughter, Queer Girl, it has met with such acclaim, even from the Agency itself, she is enjoying the transition from living with shame and secrets to “having the opportunity to be a public personality.” She has been on book tours all over the US and has even met other spy daughters who are writers.

Meanwhile, she continues teaching, writing, swimming and embracing life and her wife, Susan Beneville, with all its ups and downs. It is a privilege to know Leslie, to share her love of Greece, and to have read her book not once but twice, with enormous admiration at the way she has constructed it, laid bare her thoughts and emotions, and invested them with so much love, understanding and compassion.

Spy Daughter, Queer Girl published by Latah Books is available on Amazon and on Audible. Leslie Absher’s poignant memoir on growing up in Greece as the dauhter of a CIA agent during Greece’s military dictatorship, Spy Daughter, Queer Girl will be published in Greek by Brainfood Media. The author will be in conversation with the amazing poet/Vima columnist Crystalli Glyniadaki at Kombrai Books in Exarcheia on Wednesday, November 13, 2024 at 7 pm.