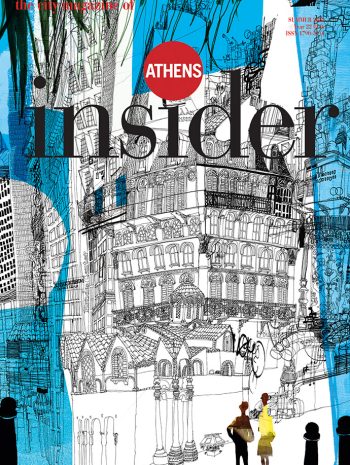

Michael Landy: The Mirror Man

Michael Landy was one of the Young British Artists who transformed the international art scene of the 1990s. Now, he has installed himself in Athens to hold up a mirror to the people of Greece. Amanda Dardanis meets the artist most famous for once destroying everything he owned to talk about his creative legacy and why Athens now has the artistic edge over London.

A member of the infamous “Class of ’88”, Michael Landy graduated from London’s prestigious Goldsmiths in the same sweep as those artistic juggernauts Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin.

While that bawdy trio dominated headlines for much of the Nineties, Landy’s time would come a little later. It wasn’t until 2001, with his epic performance piece, Break Down, where he systematically destroyed every last one of his belongings in London’s Oxford Street to the strains of Joy Division and David Bowie, that things really took off for this creatively-gifted son of an Irish immigrant – hereafter known as “The Man Who Destroyed Everything”. “Everything”, it turned out, was 7,227 items, including precious family heirlooms, love letters, clothes, personal documents like his birth certificate – even his Saab Turbo.

Landy’s unforgettable visual treatise on what many saw as the morality of consumerism ignited our curiosity, our incredulity, and our emotions. A massive media response followed (Landy was profiled in Newsweek, lampooned by Viz, and became the subject of a BBC documentary). So extreme was the public reaction to his social experiment, meanwhile, that he was offered counseling by both psychiatrists and priests.

To many of us, the idea that someone could simply walk away with nothing but the blue boilersuit on his back was deeply unsettling.

It’s now 16 years on, and Michael Landy, when we meet, is back in a blue boilersuit. He’s in Athens for his latest project Breaking News to take our collective temperature. To find out what makes the Greek public tick by asking us to send in slogans, quotes, graffiti or images, which he then transforms into paintings and drawings via his own filter. Through these aphorisms, Landy is hoping to wiretap the voice of the city.

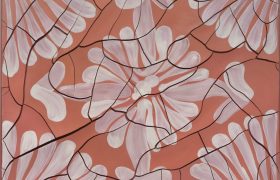

While we talk, we take a tour of the fourth floor of the Diplarios School, an artfully-dilapidated neo-classical building in central Athens. The maze-like nest of empty rooms is slowly coming alive with drawings, big and little; all blue and white (to signify “the sky, the sea, the flag of Greece”), in what’s already shaping up as a rich cultural canvas. I spy messages as varied as “Merkel Go Home” to “I love Feta”. There’s a fierce archangel bearing firearms and former prime minister Charilaos Trikoupis famously declaring, “Regretfully, we are bankrupt.”

‘We’ve had lots of “oxis” too,’ observes Landy, who at 53, still possesses a youthful form and vigour, despite the greying temples. “I’m told the Greeks like to say “no”, he deadpans.

Many of Landy’s projects, including this one, concern themselves with our common humanity and are heavily shaped by public collaboration. In 2010, he turned a South London gallery into a 130,000 gallon scrapheap he called Art Bin where he trashed other people’s artistic failures selected from online submissions. His high-profile Acts of Kindness, meanwhile, celebrated the ordinary acts of generosity and compassion that occur between strangers every day on the London Tube.

His 2013 installation Saints Alive for the British National Gallery also thrust him back into the limelight. While artist in residence at the typically conservative institution, Landy gruesomely transfigured sculptures of Christian saints to depict them eternally re-living their violent trials.

In person, Landy is great company. He’s relaxed, funny and self-deprecating, with none of the tightly-coiled temperament or referential tendencies you might expect of someone with his artistic pedigree. One senses that it’s the work and the community interaction that propels him far more than the attention.

Tell us what motivated you to stage Breaking News here in Athens?

I’m very interested in what makes us human apart from what we have to offer financially. So I was interested in asking the Greek public to tell me what makes them angry or happy or sad in their everyday lives, rather than hearing from politicians and the media.

Is this your first time in Athens?

No. In 2011, I made a credit card destroying machine for the Frieze Art Fair. About 500 people volunteered to let me destroy their cards. In return, the machine also made abstract drawings on paper that I would sign. Two years later, I was invited to show the work again down in Piraeus in an old abandoned building. Afterwards, I started to talk to NEON about doing this project.

How would you describe the energy here?

When you arrive in Athens, the energy feels really good, really creative. London has just become too swanky in a way. And it’s become kind of dull. Once you kick out all the young creative people, which is what’s happened, you end up with some kind of glorified museum. You need young people to come up with new ideas to re-generate a city.

So you believe that London has lost some of its allure for young up-and-coming artists?

It’s a shame about London because when I left art school in the late 80s you could still squat. We could find run-down, semi-industrial buildings and spaces to create in; buildings that hadn’t been re-developed yet. Whereas here in Athens, things are peeling everywhere and are quite dilapidated. I’ve started to become fixated on all the peeling paint in Athens! As a child in post-war Britain, I remember picking at the peeling paint you’d still see on buildings, even in the 60s. And that’s what’s so exciting about Athens. Coming here you feel a real vibrancy.

Has Athens creatively inspired you so far?

It has. Apparently, Athens is the new Berlin. I look out of the window (of this studio) and you don’t know whether people are living in the buildings opposite. Are they occupied or unoccupied? In London, every inch of land has been filled with luxury flats and shops and all that wasteland has gone. But as an artist, you need those spaces to put on exhibitions and have studios. There is a real sense of freedom here. That’s what I really like. That and the great vibe.

Are you getting some interesting submissions?

We’ve had to decline quite a few pictures of cats and scenic views. That’s not what this is about. But we’re getting some great social and political things. I can either take them literally, or take part of their image and reproduce it. Or I’ll take some of their graffiti text and we’ll pin it up in the school. (I’m having to rely on my assistants to tell me about word play and context because I don’t speak a word of Greek!).

Is it hard to live down a project like Break Down? Do you resent people always returning to it as your great magnus opus?

No, I dealt with that years ago. I know that Break Down is the thing most people want to talk about. Because it’s obviously quite extreme to destroy all your worldly belongings in front of complete strangers!

Why do you think people are still so intrigued by that particular social experiment? Perhaps because it forces us to examine our own unhealthy relationships with our possessions?

Reading about it (what I was doing) and witnessing it was a completely different thing. All you could come away with is the actual experience. People nicked stuff. One bloke tried to take a valuable print of mine to sell but my mate got hold of the other end, and it was like a tug of war. This guy said, “But he doesn’t want it anymore anyway”, which wasn’t the point.

What did your parents think of it all?

It was hard for my parents. They came to Britain to build a better life for themselves and their children and suddenly they have to see their son destroying all their belongings. But I didn’t destroy my name. That’s what someone said to me once. I thought that was a really clever thing to say. I didn’t change my name and there’s no denying that I became a better known artist afterwards because of that.

Is it true that you were offered counselling by both priests and psychiatrists while you were in the process of destroying everything?

I was offered help by all sorts of people! But it was actually the happiest two weeks of my life. I really loved going in every day. We’d play my record collection and we had a resident DJ. There was a sense of elation. Destroying things, taking things back to how we made them in the first place. It was like witnessing my own death. I had people turning up who I hadn’t seen in years. My mum was crying. So she had to go. I had to throw my own mum out.

What was the hardest thing to part with?

My dad’s sheepskin coat was the hardest thing to destroy. I subsequently made a piece of art about it.

What was your first waking thought the next day?

Well, I was hungover, so I was a bit paranoid. Suddenly you had to create your life over again. I had to go and get another birth certificate, a duplicate passport…

Did people expect you to live like an impoverished saint afterwards?

Yeah. But that’s not what it was about. I’m not a saint and I wasn’t pretending to go and live out the rest of my days on a desert island somewhere. It was a work of art, not a way of life.

Do people ever ask you to re-create Break Down?

Someone asked me only yesterday! But it’s a once in your lifetime gig. You can’t escape consumerism. It’s inescapable. We judge people by how much they own and possess and we’re jealous of them. But I’ve also done projects on Saint Francis of Assisi where he sees people in rags and he’s kind of envious of their poverty.

Oh yes, your infamous Saints Alive project at the National Gallery. Did they know what they were getting themselves into?

When they phoned me up about going there, I was destroying things everywhere, and I thought they must be pulling my leg. They said I could look at the collection in the evening by myself. I don’t think they really trusted me. I mean, I’m not going to destroy a Velazquez! So they had a guard following me around with a key in case I got up to no good.

What was your artistic inspiration for Saints Alive?

Well, I don’t paint. So I had to find another way of going about things. I come from an Irish Catholic background so I started to look at saints and Christian iconography. They were a violent lot. Saint Apollonia patron saint of dentists was tortured by having her teeth pulled out. Saint Gerome beat his chest with a rock.

Your Break Down project is especially poignant in Greece where Greeks have, by necessity, had to radically re-imagine themselves and their previous consumption…

People here have had to come to terms with the fact that they’ll never have that kind of wealth again. Except for the younger people. This is just normality for them now. This has been their backdrop for years. I’ve got about eight young Greeks working for me here and they are all committed to staying here.

Add Breaking News Tagline: From last issue

How you can get involved

The exhibition space at Diplarios School, Platea Theatrou 3, Athens, will open to the public on March 30 and the installation will be completed on June 11, 2017. Afterwards, participants may retrieve their work. Submit your images in digital format via the NEON website here or as hard copy in the exhibition space, on Fridays from 12pm to 7pm. You can also follow the work in progress on Instagram @breakingnewsathens. Open from Thursday-Sunday from 12-8pm.

Breaking News – Athens

30.3-11.06.2017, Διπλάρειος Σχολή | Πλατεία Θεάτρου 3

Image Credits

Breaking News – Athens, Michael Landy, Workshop View, © Photograph Stefanos Giannoulis, Courtesy NEON